Pedro Albizu Campos was born poor in the Barrio Tenerías section of Ponce, Puerto Rico. His mother Juliana died when he was four years old, his father disowned him, and Albizu was raised by his maternal Aunt Rosa.

He went barefoot most of his childhood, but he was a brilliant student. He won multiple scholarships and was the first Puerto Rican to graduate from Harvard College. Albizu went on to graduate from Harvard Law School, and returned to his hometown of Ponce, Puerto Rico – where he defended hundreds of poor and indigent clients and became president of the Nationalist Party.

In 1931, Albizu defended a Nationalist named Luis Velasquez who, during a political dispute, had slapped the Chief Justice of the Puerto Rico Supreme Court. This judge was named Emilio Del Toro.

The actor Benicio Del Toro is a member of this family: a highly respected family of lawyers and jurists.

The Del Toro case went to the U.S. Court of Appeals (1st Circuit). When Albizu won, it became known as “la bofetá de Velasquez” (Velasquez’s slap in the face).

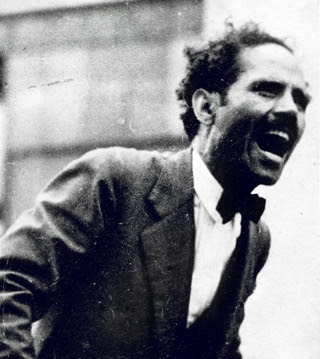

Albizu Campos speaks to sugar cane workers

The U.S. paid no attention to Albizu until 1934, when he led an island-wide agricultural strike that raised the sugar cane workers’ wages from 45 cents to $1.50 per 12-hour day.

Sugar cane workers on strike in Yabucoa

After winning the strike, Albizu became famous throughout Puerto Rico and the crowds around him kept growing.

Albizu Campos speaks at the University of Puerto Rico in Rio Piedras

These policemen and the FBI started following Albizu Campos all over the island. They watched his home, intercepted his mail, interrogated his neighbors, and arrested members of his Nationalist Party.

Albizu even began to receive death threats. Shots were fired into his home.

Policeman with a tommy gun, issued by Gov. Winship

It became known as the Rio Piedras Massacre.

War Against All Puerto Ricans

On October 29, 1935, when asked about the Rio Piedras Massacre at a press conference, Winship’s Chief of Police E. Francis Riggs uttered his famous words. Police Chief Riggs declared to the reporters that if Albizu Campos continued his agitation:

“There will be war to the death against all Puerto Ricans.”

The newspapers all reported the Police Chief’s words, the very next day. The entire island heard about this “war against all Puerto Ricans,” and became understandably fearful.Then on February 23, 1936, two more Nationalists were arrested and dragged into a San Juan police precinct, then executed inside the precinct.

Elias Beauchamp, a few hours before his police execution

Funeral for the slain Nationalists. El Imparcial, Feb. 25, 1936

A few days later, in March 1936, Albizu was arrested and tried for conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government. On the day of the verdict (July 31, 1936) every room, hallway and staircase in the José Toledo Federal Building was jammed with U.S. soldiers.

The surrounding streets were all blockaded.

FBI agents mingled with the crowds.

National Guardsmen roamed the halls.

In the courtroom itself, more than half the spectators were policemen and plainclothes detectives.

U.S. military commanders from Camp Santiago sat in the front row as the jury delivered its verdict: ten years imprisonment for Albizu Campos. But that was only the beginning. From that day in 1936, Albizu lived another 29 years. 25 of those 29 years were spent in prison.

He was arrested in 1936, and sent to the USP Atlanta Penitentiary in 1937.

USP Atlanta cell block

Arrested and jailed in 1954.

At one point Albizu told his wife, and many historians agree, that “the Americans knew what they were doing – they needed me off this island right away. Six more months in 1936, and we’d have gotten our independence.”

In addition to his 25 years’ imprisonment, during the few years that he was out of prison (only four years) Albizu was surrounded 24 hours a day by FBI agents. They interrogated anyone who visited him, spoke to him, or mailed him a letter.

They tapped his phone.

They developed a secret FBI file over a period of thirty years, which contained over 20,000 pages of surveillance information from 1936 through1965.

They even passed a special anti-speech law just for him – a few months after his release from prison in December 1947.

Law 53 – The Gag Law

On June 10, 1948, they passed Law 53, otherwise known as La Ley de la Mordaza (Law of the Muzzle). This law was nearly a word-for-word translation of Section 2 of the U.S. anti-Communist Smith Act, and it authorized police and FBI to stop anyone on the street and invade any Puerto Rican home, particularly Nationalist homes.

It was a gag law. It prohibited the singing of a patriotic tune; or to own or display a Puerto Rican flag anywhere, even in one’s own home, no matter how large or small.

It also prohibited any speech against the U.S. government or in favor of Puerto Rican independence; or to print, publish, sell or exhibit any material about independence; or to organize any society, group or assembly of people on behalf of independence. Anyone found guilty of disobeying the law could be sentenced to ten years imprisonment, a fine of $10,000 dollars, or both.Police find dangerous Puerto Rican flags

Police find more dangerous Puerto Rican flags

Albizu at Sixto Escobar Stadium

They met him at the San Juan waterfront.

They packed into churches with him.

They marched into municipal theatres, and filled the streets of Ponce and Arecibo.

The FBI followed him everywhere, and an agent named Jack West filmed all his public speeches. Everything went into secret FBI files, known as “carpetas.”

It was a tremendous uphill battle for Albizu. The Governor of Puerto Rico, Luis Muñoz-Marín, accused him of being a communist, a fascist, and a terrorist. The U.S. military now controlled 13% of Puerto Rico’s land.

It was using the islands of Vieques and Culebras for target practice, exploding 5 million pounds of ordnance per year.

Roosevelt Roads Naval Air Base covered 32,000 acres and three harbors, and was the largest naval facility in the world. Camp Santiago occupied 12,789 acres in the town of Salinas. Ramey Air Base covered 3,796 acres in Aguadilla. Fort Buchanan had 4,500 acres in metropolitan San Juan with its own pier facilities, ammunition storage areas, and an extensive railroad network into San Juan Bay.

Map of U.S. military Installations in Puerto Rico (disclosed locations) 1950-1960

US military celebrate their annual July 4th parade in Old San Juan

The October 1950 Revolution

On the weekend of October 30, 1950, the Nationalist Party waged a revolution against the United States. Gunfights roared in eight towns. Police stations were burned down. The Republic of Puerto Rico was declared in the town of Jayuya. Assassination attempts were made against Pres. Harry Truman and Governor Luis Muñoz-Marín.

In order to suppress this revolt the U.S. bombed two towns, mobilized 5,000 National Guardsmen, killed dozens of Nationalists, and arrested 3,000 Puerto Ricans. Albizu Campos was arrested and jailed in La Princesa.

Prison TortureMass arrests in San Juan

A growing body of evidence indicates that, for a number of years in prison, Albizu Campos was subjected to lethal doses of radiation which caused burns and welts all over his body, and caused a cerebral thrombosis in 1957.

Albizu covered his head and body with wet towels in order to shield himself from this radiation. The prison guards ridiculed him and called him El Rey de la Toallas – the King of the Towels. The U.S. government declared hm insane, and sent a caravan of psyciatrists to prove it. But the physical evidence of Albizu’s decay, and the testimony of other prisoners that they had also been irradiated, became difficult to ignore.

Albizu shows his burns and lesions to reporters

On May 28, 1951, the Cuban House of Representatives formally tequested that Albizu be trasferred to Cuba, in order to attend to his radiological cure.

Albizu with burnt skin, all over his body

In 1953 the International Writers Congress of Jose Martí sent a letter to President Eisenhower on behalf of Albizu. It was sugned by 28 prominent writers, journalists and intellectuals from 11 countries.

All of these were ignored, until Albzu suffered a cerebral thrombosis in Laq Princesa, which left paralyzed the right side of his body for the rest of his life, and rendered him mute.

Albizu Campos was not longer able to speak. They had silenced him forever.

Eventually, the U.S. radiation experiments became common knowledge. A woman named Eileen Welsome wrote a book titled the Plutonium Files, a newspaper series called The Plutonium Experiment, and she received the Pulitzer Prize for it. The U.S. Dept. of Energy has admitted to conducting these radiation experiments, and has paid monetary compensation to many of the grieving families.

After many years, the demand continues for a complete investigation of the radiation torture of Albizu Campos.

Funeral Rites and Burial

Shortly before Albizu Campos’ death, Ernesto “Che” Guevara stood before the United Nations General Assembly and gave this speech on his behalf:

“Albizu Campos is a symbol of the as yet unfree but indomitable Latin America. Years and years of prison, almost unbearable pressures in jail, mental torture, solitude, total isolation from his people and his family, the insolence of the conqueror and its lackeys in the land of his birth – nothing broke his will.” (Dec. 11, 1964)

Albizu Campos died on April 21, 1965. His family received hundreds of telegrams, cables and letters from around the world. The Senate and House of Representatives of Puerto Rico commemorated him in both chambers, and the Parliament of Venezuela observed five minutes of silence in his memory.The newspaper El Imparcial ran an immediate special edition, with Albizu on the front cover.

Before the burial artists made an alginate mold of Albizu’s face, for the sculptures and statues that would be built in his honor.

Government officials, journalists and friends from every country in Latin America arrived to attend the final services. Before Albizu’s burial on April 25, over 100,000 people passed by his funeral casket.

An honor guard accompanied the funeral casket from the Ateneo Puertorriqueño. The streets of San Juan were lined with 75,000 black ribbons that had been tied to trees, cars, lamp posts, benches and street signs, all the way to the cemetery.

Honor guard for Albizu Campos in San Juan, Puerto Rico

His burial was officiated by Bishop Antulio Parilla and two priests, each representing the three largest cathedrals in Puerto Rico.

Funeral ceremonies for Pedro Albizu Campos

Remembrance and Legacy

Over the fifty years following his death, parks and plazas have been named after Albizu Campos, all throughout Puerto Rico. Nearly every municipality has a Calle Pedro Albizu Campos (Pedro Albizu Campos Street). Five public schools were named after him.

In his hometown of Ponce, the Parque Pedro Albizu Campos (Pedro Albizu Campos Park) contains a life-size statue of him, and annual memorial services are held there on his birthday. In the town of Salinas there is a Plaza Monumento Don Pedro Albizu Campos – a plaza and a nine-foot statue dedicated to his memory.

Schools and community centers were also named after Albizu Campos in New York City and Chicago.

Annual parades are held in his honor, both in Puerto Rico and the mainland United States.

Albizu Campos will always be remembered as one of the great patriots in Puerto Rican history – who bravely and eloquently reminded the United States of their own founding principles, and spent 25 years in jail for doing so.

Throughout his entire life, he fought for the improvement of labor conditions for workers and jíbaros (country people), for a more accurate assessment of the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States, and an awareness by the political establishment in Washington, D.C. of this colonial relationship. His legacy is that of a lifetime of sacrifice – for the building of a Puerto Rican nation.

It is a legacy of resistance to colonial rule.

"Real leaders must be ready to sacrifice all for the freedom of their people".

Nelson Mandela

Selected Footnotes.The following notes pertain to the Total Body Irradiation (TBI) procedure which the U.S. government inflicted on Pedro Albizu Campos, while imprisoned in La Princesa. It is a controversial area which deserves the fullest documentation and inquiry.

1. Subcommittee on Energy Conservation and Power, U.S. House of Representatives, “American Nuclear Guinea Pigs: Three Decades of Radiation Experiments on U.S. Citizens,” 99th Congress, 2nd Session, November 1986, pp. 1-17.

2. Philip J. Hilts, “U.S. to Settle for $4.8 Million in Suits on Radiation Testing,” New York Times, November 20, 1996.

3. “Count of Subjects in Radiation Experiments Is Raised to 16,000,” New York Times, August 20, 1995.

4. Keith Schneider, “Secret Nuclear Research on People Comes to Light,” New York Times, December 17, 1993.

5. Matthew L. Wald, “Rule Adopted to Prohibit Secret Tests on Humans,” New York Times, March 29, 1997.

6. Eileen Welsome, The Plutonium Files (New York: Random House, 1999).

7. Juan Gonzalez, “A Lonely Voice Finally Heard,” New York Daily News, January 12, 1994.

8. Pedro Aponte Vásquez, ¡Yo Acuso! Y lo que Pasó Despues (Bayamón, PR: Movimiento Ecuménico Nacional de P.R., Inc., 1985)

9. Howard L. Rosenberg, Atomic Soldiers: American Victims of Nuclear Experiments (Boston: Beacon Press, 1980).

2. Philip J. Hilts, “U.S. to Settle for $4.8 Million in Suits on Radiation Testing,” New York Times, November 20, 1996.

3. “Count of Subjects in Radiation Experiments Is Raised to 16,000,” New York Times, August 20, 1995.

4. Keith Schneider, “Secret Nuclear Research on People Comes to Light,” New York Times, December 17, 1993.

5. Matthew L. Wald, “Rule Adopted to Prohibit Secret Tests on Humans,” New York Times, March 29, 1997.

6. Eileen Welsome, The Plutonium Files (New York: Random House, 1999).

7. Juan Gonzalez, “A Lonely Voice Finally Heard,” New York Daily News, January 12, 1994.

8. Pedro Aponte Vásquez, ¡Yo Acuso! Y lo que Pasó Despues (Bayamón, PR: Movimiento Ecuménico Nacional de P.R., Inc., 1985)

9. Howard L. Rosenberg, Atomic Soldiers: American Victims of Nuclear Experiments (Boston: Beacon Press, 1980).

A much more extensive discussion, footnotes, citations, and bibliography all appear in the book War Against All Puerto Ricans…

Click below to hear an hour interview with the author of this book.

http://www.blogtalkradio.com/latinorebels/2015/04/13/war-against-all-puerto-ricans-a-conversation-with-nelson-a-denis

Click below to hear an hour interview with the author of this book.

http://www.blogtalkradio.com/latinorebels/2015/04/13/war-against-all-puerto-ricans-a-conversation-with-nelson-a-denis

Nelson A. Denis will be at the book store in Old San Juan on

Monday, May 18 at 2 PM. Come and meet him!

Click on the link below to see Nelson talking about his book at Hostos Community College.

https://youtu.be/bhRrtgio8LU?t=189

Click on the link below to see Nelson talking about his book at Hostos Community College.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario